Babies Are Out Of Style & Why It Makes A Difference

The numbers are in. Babies are out. Out of style that is. Data reported by the Centers for Disease Control this month indicates that the United States had the fewest number of children in 2020 since 1979. Moreover, in demographic geek speak, the lowest birth rate since…well… since the United States collected data on how many children each female has over her lifetime.

We have seen this before. Wars, famine, economic downturn, financial uncertainty, and pandemic all depress being in the mood, the mood to have children of course. However, as crises ebb and conditions improve, there is a traditional uptick in the number of children born. After all, there would be no Baby Boomers without the celebratory return of soldiers from battle and the desire to have children after WWII.

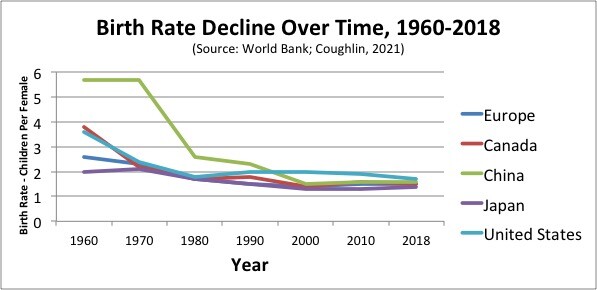

Always seeking to be number one, the United States is now apparently in competition with the rest of the industrialized world (and many developing economies) in a race of how low can we go. According to the CDC the United States birth rate is now an anemic 1.6 children per female, compared to the 2.1 children per female needed to simply maintain population status quo. While among the youngest of the global geriatric set, the record low birth rate puts us in league with aging and shrinking European and Asian nations. Note in the chart below, the birth rate of the populations highlighted are under the replacement rate of 2.1 children per female.

The birth dearth across many of the world's largest economies is no longer a blip on the demographer’s radar; it is a trend that has been in the making for decades. It is as much a critical part of the longevity economy as the aging of society. Our nations, communities, and markets are aging because of the growing number of older people and because we have cut the supply of younger people.

The answer to the question, why no kids, is for a future #LongevityEconomy article. Even if we turn the baby machine back on, full throttle, the impact of not having children for decades has set into motion a societal shift in institutions, markets, and the many things we take for granted and don’t even think about – most of which were built around the assumption of a steady and ever-growing number of children.

Let's ponder one big institutional shift. How will fewer children affect schools?

Communities that have recently replaced aging elementary and secondary school infrastructure to accommodate today’s student numbers may find more classroom seats than children in a few short years. For those communities contemplating new construction, they may want to reimagine how the buildings designed today might be made for ‘dual use’ tomorrow. The shift from many younger students to many older people might be an opportunity to consider how school infrastructure, from the libraries, gyms, workshops, etc. can be enjoyed by an entire community, regardless of age and across the lifespan.

Let’s not stop at education institutions for students under age 18. My industry, higher education, is not immune. There has been a steady decline in the number of students enrolling in college. Some choose not to enroll due to cost, some because of perceived long-term value, others because they are doing well without the degree.

Long before the pandemic, the flat to declining number of young people has eroded the pool of possible students that many colleges, particularly smaller to mid-size colleges can draw from. NPR reports that east coast stalwart institutions such as Trinity College, founded in 1823, are working harder to find the students they want. The same NPR report describes how the President of one small school based in Boston’s suburbs, Pine Manor College, travels across the country in search of students. The University of Maine has gone as far as to offer in-state tuition to out-of-state and international students to achieve the enrollment yields they seek.

The big shift in demographics may require many institutions to focus more on upskilling of older workers and lifelong learning not as an ancillary operation, but as a central ‘business’ in the business of higher education. How might such a shift change curricula, physical plant, and amenities on college campuses?

Other institutions that rely on a steady flow of young people may have to compete even harder for the talent they need. Employers may find abundant numbers of young people pursuing some professions and empty tractors seats, trucks, assembly lines, and even hospital hallways in other jobs.

Even the military must take note. According to a report in the Military Times “the Army [in 2018] sought an ambitious 80,000 new recruits. They dropped that goal to 76,500 but still only came in at 70,000 by the end of the year.”

States will compete for people. The northern tier of New England, parts of the midwest, and selected other states are losing population. Fewer people may mean possible worker shortages, more pressure on the taxpayers that remain, and even a shift in political power. Note that in the recent US Census results California, a country unto itself, actually lost a seat in the US House of Representatives. Will we see tax holidays for people to move to a state the way states cut deals for businesses to locate facilities? Maine, Vermont, Oklahoma, Alaska, among others, will pay as much as $10,000 for young people to move to their state.

The shift in markets will become obvious. Long before pandemic puppies became a thing, there were reports of people spending more money on pets than children. Retailers are reallocating floor space from kids wear to pet toys. I will have more to say about this in a future article.

The birth dearth has other implications. How might fewer children in a family change the automobile? Not that I would miss seeing minivans on the road, but is the future of the car even smaller?

Speaking of small, will the housing stock that Boomers are hoping to someday flip to pay for beach walks, golf memberships, and long-term care going to attract younger buyers that do not find the number of bedrooms or the quality of the schools of interest, let alone affordable? See more on this in my Forbes piece addressing the topic.

How about big box stores? Will we need big box shopping to supply smaller households? Without hungry teenagers a loaf of bread, half the size of today’s typical package, may last a week-plus with only one or two adults in a household. What might be the implications for countless consumer packaged goods? Will Johnson’s Baby Shampoo be renamed to simply Johnson’s…Shampoo?

The #LongevityEconomy is not just about the “old,” it includes the ripple effects of disruptive demographic across the life course. Lower birthrates will shift nearly everything society generally, and business specifically, has assumed over the last century. Fewer younger people will compel business and policymakers to focus more on older people as workers, consumers, and voters. Not as a legal requirement or nicety as many do today, but as a necessity to ensure that their organization maintains the skills and knowledge necessary to compete, to tap the inherent growth and wealth of the older consumer segment, and to respond to the demands of a highly efficacious, but older, electorate.